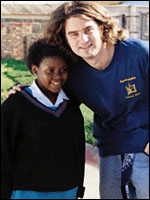

Co-founder and Co-president of Ubuntu Education Fund, Jacob Lief

Born in New York, Jacob Lief first became interested in South Africa while growing up in London, England. In 1994 he traveled to South Africa to observe the nation's first free elections, with a delegation of teachers and students from around the world. Inspired, Jacob continued to pursue his interest in South Africa at the University of Pennsylvania under the guidance of Dr. Mary Frances Berry, Chairperson of the Commission on Civil Rights and a major figure in the Free South Africa Movement. In his third year of University, Jacob returned to South Africa where he met Malizole Banks Gwaxula, a teacher living and working in the Port Elizabeth Townships. In 1999, Jacob and Malizole founded Ubuntu Education Fund (www.Ubuntufund.org), a nonprofit organization dedicated to working with the people of the Eastern Cape Province to develop quality education and healthy communities in the New South Africa. Over the past nine years, Jacob has served as President of Ubuntu and worked to develop Ubuntu from a small fund supplying basic educational materials to an international development organization creating sustainable health and education initiatives. Today Ubuntu provides over 40,000 orphaned and vulnerable children life-saving HIV support services and essential educational resources.

Jacob Lief is someone that I would characterize as being charmingly unaware of the extraordinary contribution that he is making in other people’s lives everyday. And yet, at the same time he seems painfully aware of just how urgently people need what he has to give and how so many more are still hoping.

DR: Tell me about your life and your work.

JL: To understand Ubuntu Education Fund and who I am as a person, I've got to look at my first experiences with South Africa.

I am an American, although I was raised in the UK. I got involved with the Free South Africa Movement. In 1994, during their first Democratic elections, they were taking students from around the world to observe the transition and I went. We met with all of these incredible freedom fighters who had done time on Robben Island with Nelson Mandela. We also met people on the far right who were trying to impose apartheid on South Africa.

I'll tell you the story that changed my life...

I met this woman in Orlando West in Soweto, one of the most famous townships in South Africa, outside of Johannesburg. Millions of people live there. I met this woman who was eighty five years old. She had been waiting in line for five days to vote. When I asked her how someone could wait in line for five days to vote, she just smiled at me, tapped me on the should and said,

"Boy, it's been eighty five years, not five days".

I just remember being there amongst all of those shacks that were people's homes and it just hit me right then that I don't think I'd ever really thought about freedom in that context. I could see that I took so much for granted. Right there I made a commitment to myself that I would become part of the new South Africa. I was only seventeen.

I went on to study at the University of Pennsylvania. There was a professor there named Mary Frances Berry. I was getting involved during my first year and a half at Penn in West Philadelphia community projects and getting more and more frustrated with the lack of parental support of the students we were working with and how much money I saw moving through these organizations versus how little was coming out.

I started working with Mary Frances Berry, who was part of the Free South Africa Movement and the U.S, Commissioner on civil rights and the first woman and the first Black woman to ever be president of a major university. She sponsored me to go back to South Africa. So, I went to Cape Town in 1997 to work for an organization and in spite of that fact that it turned out to be a complete scam after she had stuck her neck out for me, I made my way up to an area called Port Elizabeth where a guy invited me to one of the townships.

I'd always read that a white guy shouldn't be going to the townships but I went with this guy to a shabin.

DR: What's a shabin?

JL: During apartheid Black people were not allowed to have bars or taverns. They were not allowed to gather in groups of more than five people. Shabins were sort of the illegal gathering place.

DR: That is so weird to imagine...

OUR STORY

Two men of different race and generation - one South African, one American - are partners in a common cause. From a chance meeting in 1998 in New Brighton Township, South Africa, Banks Gwaxula and Jacob Lief came to realize that they shared more than a common interest in soccer. The two shared an abiding belief in the power of education.

Banks invited Jacob, a travelling student, to live in his home as family and work with him as a teacher in his township school. In the townships, Jacob witnessed people overcoming the desperation of poverty through the power of community. He learned that townships schools lacked resources taken for granted in even the poorest communities in the United States. Classrooms made out of abandoned shipping containers held as many as 60 students at a time. Children shared few desks and fewer chairs. Teachers taught in front of blank boards in schools that had not owned a piece of chalk in years. Yet students with neither books nor pencils listened attentively to their teachers for hours on end. For despite the immeasurable hardships, communities remained dedicated to the belief that education would allow their children to overcome Apartheid's legacy of poverty, disease and inequality.

Six months after their meeting, Banks and Jacob founded Ubuntu Education Fund. Today Ubuntu is reaching over 40,000 children with life-saving health and educational resources and services. We are proud of the numbers, but most of all we are proud of our staff and the children who are taking advantage of being the first generation of free South Africans.

Along the way Banks and Jacob were joined by dozens of people dedicated to making their community a better place. Ubuntu invested in training them, and every day our communities reap the rewards. A bond between two people has become a family of 50 employees and a life force for entire communities. A small grassroots project has become an organization with a strategic plan for long-term, sustainable development. We began in a small storage place in an elementary school. Our new centrally located 2500 square foot headquarters in Zwide Township is a symbol of hope. Our first strategy was to hold meetings amongst community members and listen to their ideas. We have never changed course, we have never stopped meeting and listening. We now have a model for development and methods of evaluating all of our initiatives.

Those same children who inspired Jacob and Banks to start Ubuntu Education Fund in 1999 are now about to graduate from high school. We have made a difference in their lives. Where we saw decaying infrastructure, we now see libraries and computer centers-where they saw hope, they now see true progress.

JL: Yeah. It's incredible.

These were the meeting places where people got together to talk politics; to talk about everything. This was "the meeting place" but they were illegal and they would do raids on them.

So, when we walked into this shabin, the guy I was with sat me down next to a guy who spoke English so he could talk to this "young American kid". The guy he sat me down next to was a man named Banks Gwaxula.

Banks and I instantly hit it off. He shared with me that he was a school teacher and we just bonded. I told him that I was doing a school project and he invited me to come and work at his school. I told him that I needed a place to live and that night I moved in with Banks and his family in New Brighton Township.

This was only three years after apartheid so obviously white people weren't around in the townships. You'd think that I would've been sort of this symbol of the past. That is what was so amazing about this place! People were more concerned about who I was as a person. I had never experienced that anywhere on any side. It wasn't that people weren't labeling and that race wasn't at the forefront of every discussion, there was just a deeper sense of humanity.

I asked Banks,

"What is this thing that you people have? I've never seen it before."

When he asked me what I meant, I told him that when I go into anyone's home I am offered tea.

"You invited me home after you knew me for three hours", I said. "What was it that had you share the little food you had? You told your son he had to share his bed with me. What is all this about?"

He said,

"That's Ubuntu."

I asked

"What's Ubuntu"?

And he told me that Ubuntu is how you treat people. Its humanity and it doesn't matter what color your skin is or your politics or your religion.

"Shouldn't the fact that we are all human beings be enough that I should treat you like a brother?"

That was an incredible moment in my life in terms of thinking about how to treat people.

I was raised Jewish and I spent a lot of time with people that had survived the Holocaust, who to this day, will not speak to a German person - even people my age. Here, everyone I met had stories of apartheid that were terrible - family members being killed, people being beaten, apartheid just ripped apart communities at the deepest level and here, three years after the end of it, this community is saying to me

"You're a person. Shouldn't I treat you like one of my relatives?"

DR: I can see how all of this would be life changing. And so...

JL: I started working at the schools there. The schools were as terrible as you can imagine. You know, the apartheid government built these schools, these sort of large brick bunkers and there was no division just one class facing one way, another class would face the other way -- the objective of the guy who created this model was to impede learning and stifle motivation. That is how sick the system was.

DR: This is incredible...

JL: They specifically designed these schools to create generations of diggers of ditches.

DR: Wow...

JL: I started teaching at these schools and just observing and during my last two weeks there, two things happened that really led to Ubuntu starting.

The first was Banks waking me up at 4:00 in the morning to show me something.

We went walking in this area that was all shacks. There were people all around, as far as you could see, starting their morning fires so that they could boil water. There were all of these kids, eight and nine year old kids, who were holding rocks over fires and using the rocks as irons to iron their school uniforms. They were proud and wanted to look dignified to go to school. That to me was amazing because you know how we dress to go to school here - like slobs. All of these kids were ironing, but with rocks.

The other thing was that I had written to a friend asking for chalk because we didn't have any. During the last week that I was there a little box came; just a box with twelve pieces of Crayola chalk. I divided each piece in half and handed them out to the teachers and I just watched as the class just sort of came alive a little bit. It was simple.

Looking back at my experience in Philadelphia -

I knew how important the work was in Philadelphia but I could see how demotivated I was and how demotivated everyone else was. After being in South Africa I saw this chance. A fire was burning there. All kids wanted to do was learn. That was the most incredible thing. The parents were uneducated and illiterate, but they fought for their children to have a chance to go to school and the kids saw education as a way out.

DR: So how did Ubuntu actually come about?

JL: Banks and I watched as all of this money was being dumped into post-apartheid South Africa from these huge international companies and all of it was just disappearing because it was such a top down approach. That's when Banks and I decided to start an organization. We decided to call it Ubuntu Education Fund.

We spent the first six months doing nothing but listening. We went around to the communities taking notes, meeting with students, meeting with parents and teachers - you name it. We listened to anyone who would talk to us. I think our success over the last ten years is because we never stopped listening. We just keep listening.

Our goal in the beginning was to help young children access higher education, however what we saw over the last ten years is that to get our kids there, we would have to have all kinds of intervention - from health to HIV to counseling, to help our kids get there. So, we have evolved over time. The goals remain the same but our strategies have evolved.

Today we have 40,000 orphaned and vulnerable children enrolled in our program. We have sixty full time staff members down there and it's not about bringing people in who look like me or who are foreigners. It's about utilizing the incredible resources and skills that are already there.

DR: I noticed that when I watched your DVD. The strength of the community was clear to me...

JL: Yeah...we didn't try to tell everything that we do. What I always say is the most impressive thing about Ubuntu is our staff. We have sixty employees, forty of which are under thirty years old. I think that is incredible because it's dynamic and young and that goes a long way.

A lot of our work deals with young girls and women because that is the face of HIV. We have twenty five centers for young girls who have been raped or abused. We also do a lot of counseling and gender work with young boys as we try to change gender norms and de-stigmatize HIV. We feed 3,000 kids a day and that's not just some random component. Our kids aren't getting fed at home because there is no food and they are passing out in school. The feeding of the children isn't just a charitable handout it's a key aspect of keeping a child in school and focused. We grow the food in organic gardens and these are organic community gardens that are run by mothers and grandmothers in the community. It's not like we feed them through a soup kitchen.

DR: Wow Jake, the more you talk about Ubuntu, the more inspired I get. What does it mean to you personally to be able to do this kind of work?

JL: You know I never thought about it. It's sort of something I just do. It's not a job for me, it's a lifestyle. It's my life.

From a fundraising standpoint we always need more money. From a program standpoint, there are always more kids in need. This week we placed a hundred and fifty new kids into University. These are kids who have been with us for eight years who are now computer literate, who are healthy, who know how to make wise decisions and who know how to survive and thrive in a community with 40% HIV. They are going out to major universities with full scholarships and they are going to make it.

DR: How do you think that your life would be different had you not met Banks or not been introduced to this notion of Ubuntu?

JL: I am not a religious person, necessarily. There's no doubt to me that this is fate. I mean Banks happened to go for a beer on that particular night. He happened to stay until 8:30. I happened to have met this guy on a train - I mean my God!

I look back on the journey of where Ubuntu Education Fund has come from and I am amazed at how many things just "happened". Maybe all of this was supposed to "just happen".

DR: What have you learned about yourself that you may never have learned but for this journey?

JL: To be honest, I don't feel that there is anything I can't do and that confidence is getting stronger.

What we have overcome and gone through to get to where we are...I mean no one would give me money at first. When I started trying to raise money do you think anyone wanted to invest in a twenty two year old? They were like:

"Oh, that's nice. That's your cute little African project. What are you really going to do with your life?"

That's just one side of it. On the other side of it, it's:

"Well, what do you know about us? You're White America."

Everyone has always told us what we can't do; what won't work. I think its important to set your goals and just figure out how to do it. I mean it's a lot easier now to raise six million dollars a year than it was to raise our first quarter of a million dollars. Everyone wants to be a part of something successful and we are getting successful. W are good at what we do. We know how to take a child now and we know how to get them through.

The most rewarding experience about all of this is the staff. I mean the kids are terrific but the staff is remarkable and the most inspirational people I know. They keep me going.

DR: Barack Obama has this quote. It goes like this:

Focusing your life solely on making a buck shows a certain poverty of ambition. It asks too little of yourself, because it is only when you hitch your wagon to something larger than yourself, that you realize your true potential.

What do you think about that?

JL: I do a lot of public speaking and I talk to a lot of young people. My message is not "start an Ubuntu club. Come help us." It's not about that. It's about, "We can all make a difference wherever we are." It's so easy to just complain about everything. Don't we all have a responsibility to improve things?

DR: You know what made me ask you that - about the quote?

JL: What?

DR: When you were describing your level of confidence it made me wonder if some of that confidence doesn't come from the fact that you know that you are playing a high stakes game.

JL: You know, I hear it a lot about the fact that South Africa is half way around the world --

"You're American. You've got problems within in two blocks of you!"

I get a lot of crap. But what is at stake is human life and that is what Ubuntu is about. We take these kids who have literally been through hell and get then through to university so that they can be whatever they want to be. We give them a better legacy to leave. I mean helping people get out of these horrible shitty situations into a place where they can succeed, and, constantly instilling in them this concept of giving back. Also, every one of our scholarship kids in university is required, during school holidays, to come and work at our Camp Ubuntu and mentor kids and share their experience.

DR: A hundred years from now what do you want to be remembered for?

JL: I want to be remembered for doing the right thing and there are so many ways to do that. Not everyone is good at mentoring for instance. There are so many ways. Giving money away is a wonderful thing. It can be as simple as that. There is a role for everyone.

I want to be seen as somebody who played a positive role...

Thanks Jake!

Support Ubuntu Education Fund

Bring the spirit of Ubuntu into your life. Join us today!

Click here to contribute online through Network for Good.

or

Please send contributions to:

Ubuntu Education Fund

32 Broadway, Suite 414

New York, NY 10004 USA